Dinoglyphs

Viking Swords

JT PÄLIKKÖ

Bladesmith

FINLAND

FINLAND![]()

A patinated

merovingian period sword from Finland

Pattern welded blade, crossguard & pommel of wrought iron, grip is of black oak

http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

A merovingian period

broadsword after a sword found from Sweden

Six-bar pattern welded blade, hilt parts of gold plated brass & copper and ebony

wood

http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

A simple C-type viking sword with walrusivory grip http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

Iron-age sword after a

weapon found in Ristimäki, Kaarina

The blade of the sword has a pattern welded structure, a laminated steel cutting

edge

surrounds core of two double chevron bars of damascus steel

The guard and pommel of the sword are of blued steel. The grip has wooden side

plates

stregthened with a layer of cord which in turn is covered with leather

Z-type viking sword

after a weapon found from Dalarna, Sweden

The blade is forged from five pattern welded bars, the guard and pommel are of

iron,

the grip is carved from walrus ivory, pommel's decorations are of silver

A lightly patinated, simple x-type viking sword

A simple Y-type viking period sword http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

Viking weapons

Viking shield

Viking axe

Viking helmet

Viking warrior

A patinated bronze sword without the grip panels & a bronze sword with curley birch handle http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

Length 71.0 cm Overall Weight 0.950 kg

Viking sword names

Viking long sword

Viking armor

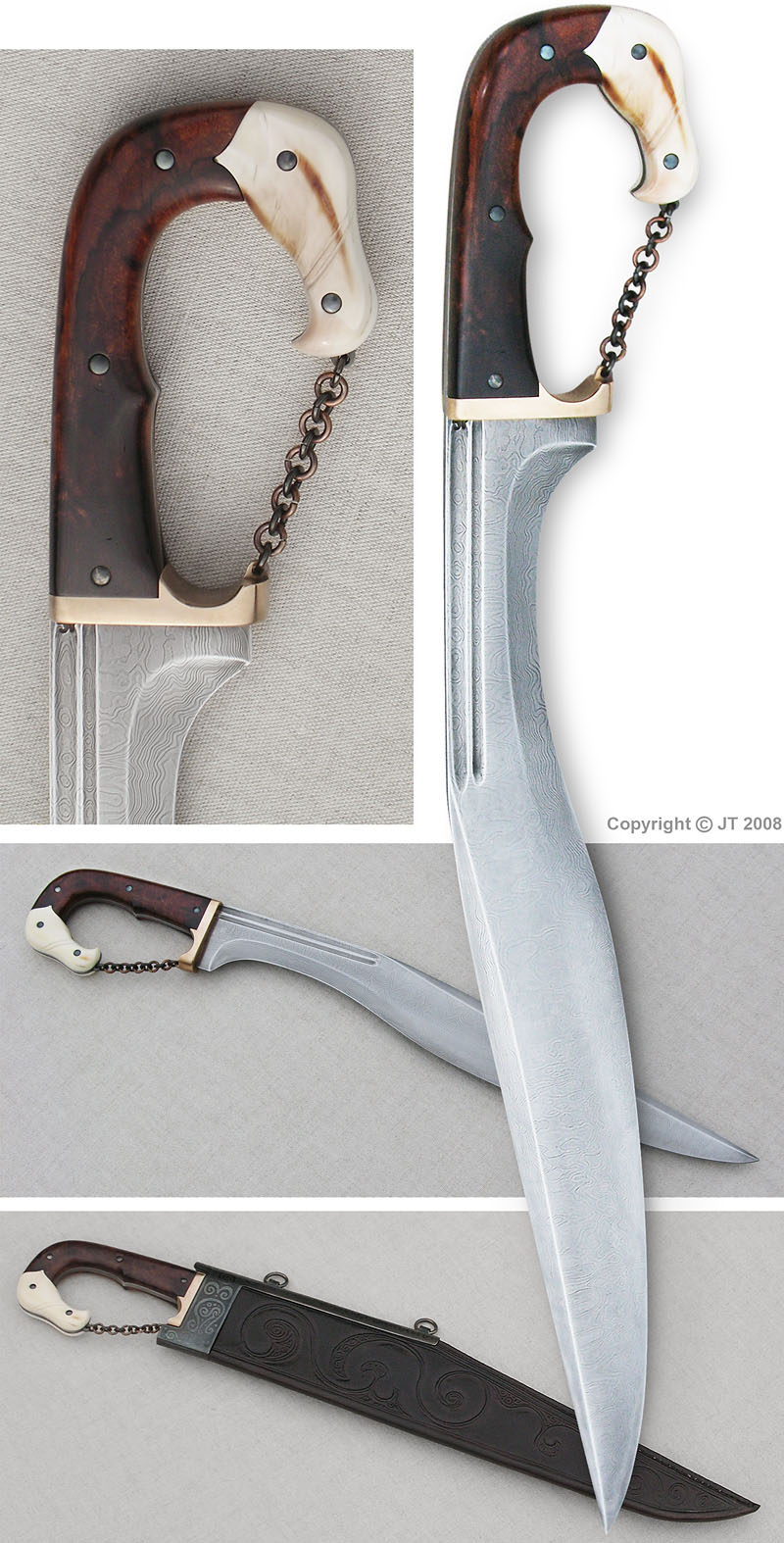

A pattern welded version of a traditional "mistress' knife"

A medieval "Falchion", single edged sword

A migration-period "Ring-sword" with damascus blade

Overall Length - 90.5 cm Length of Blade 75.0 cm - Width of Blade 4.7 cm - Width of Crossguard 9.5 cm - Overall Weight 1.015 kg - Point of Balancefrom crossguard 14.3 cm

Three miniature swords in iron-age fashion

Viking spear

When it comes to engaging in battle, I thought they used spears and fought in pairs, stretching the arms in side directions, not straight ahead.

Same thing

in the modern defense with fire arms: better to shoot to left or right to help

your pair, not straight ahead.

I've thought in the victorious Viking armour the sword-device was often

defensive rather than aggressive:

Tool and a status symbol, rather than a weapon, as worked out by a Finnish

blacksmith.

"Fransiska" early frankish throwing axe

Albion

Cambrian

Medieval war axe

Damascus viking sword

Broken sword

Sword and sandals

Norsemen

A sword with a wheel pommel from late viking period

A stiff-bladed cut-and-thrust sword from later middle-ages

Bastardi sword - 15th century longsword

An Iberian falcata, c 300 BC

An early iron-age "Akinakes" iron sword & celt-iberian "Falchata"-sword with patinated surface

A Japanese katana samurai sword

A full lenght "Katana", Japanese-style sword

A "Koshi-katana" http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

Samurai sword

Samurai

Dagger with

the hilt formed after bronze age sword hilt

The blade is composite of carbon steel and damascus steel, hilt materials are

mammoth ivory and buffalo horn

An iron age skramasax knife. The blade is forged from four pattern welded bars, the hilt is of stag antler and leather

A

Celt-Iberian single edged "falchata sword", with the blade forged of carbon

steel damascus

The hilt materials are bronze, iron wood and boar tusk,

the scabbard of the sword is leather with iron scabbard mouth

Three Roman

period gladius-swords:

first has a pattern welded blade, two others have blades forged from

springsteel,

the hilts have been made of hardwood, antler and bronze

Two Roman period

spatha-cavalry swords:

The patinated sword has a pattern welded blade and hilt made of antler

The other sword has blade forged of springsteel, hilt is made of walrus ivory

and silver

http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

A frankish-style "Skramasax"-short sword & damascus bladed "Langsax" viking-style short sword http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

An Indian-style "Tulwar"-sabre http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

A "Khyber-knife"-styled single edged short sword with damascus blade http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

Longsword with pattern welded blade, a scaled down version of a medieval two-handed sword http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

"Ravenbrand" fantasy sword. The blade and the hilt are fashioned after two different medieval swords http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

"The Beater" a fantasy-sword http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

Dragon sword

The Beater

Malleus maleficarum

Phantasy sword

Witch hammer

Hexenhammer

A light medieval hanger-sword http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

A big longsword with forged sideloops on the cross, later middle age http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

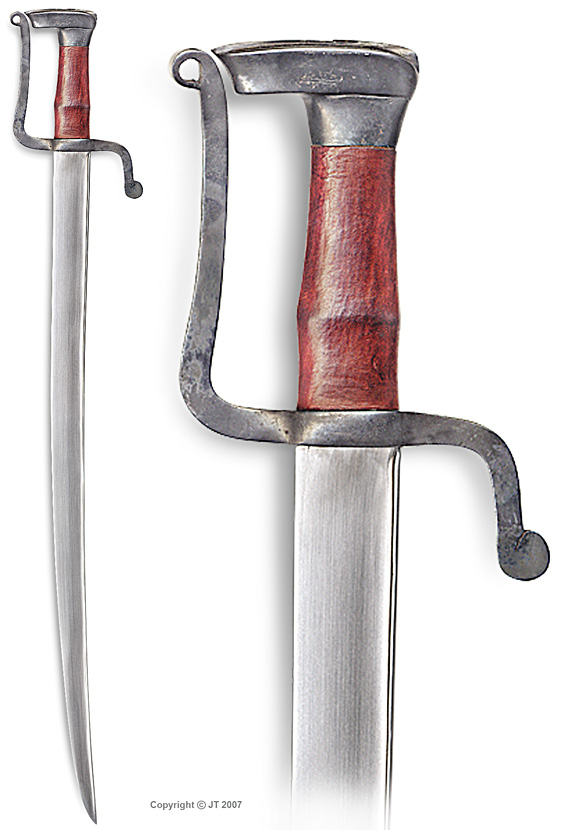

A large sized

longsword with siderings forged on the guard

The blade is forged from carbon sprinsteel, guard and pommel are forged from

mild steel,

the grip is of red oak with string wrapping and leather http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

Swiss Sabre, a two-hand sabre from renaissance period, modelled after two historical swords http://www.kp-art.fi/jt

JT PÄLIKKÖ

Master Bladesmith

Puukkoseppämestari

"Kaikki valmistamani puukot, veitset ja miekat, teen käyttöesineiksi korkealuokkaisista raaka-aineista. Puukot ja veitset ovat funktionaalisia ja ergonomisia työkaluja, joiden rakenne ja käytetyt materiaalit kestävät kovaa käyttöä. Miekat ja muut pitkät teräaseet ovat oikeita aseita - eivät seinäkoristeita. Useimmilla miekoilla on omat historialliset esikuvansa joiden luonnetta - mittoja, muotoja, ominaisuuksia - pyrin mahdollisimman tarkasti toistamaan.

Teen kaikki tuotteitteni osat ja työvaiheet itse - näin valmistamastani teräkalusta tulee linjakas, eheä kokonaisuus jota on ilo käyttää ja joka kestää käyttöä."

Miekat voivat olla

autenttisia jäljennöksiä historiallisista teristä,

tai toivomusten mukaan valmistettuja keräilykappaleita. Yllä esimerkkejä JT:n

tilaustöinä tekemistä malleista.

Scandinavian Knifemakers Guild

Xiphos

The "sword" of Ancient Greece. The weapons resembled other mid- first millennium BC iron swords (e.g. of the Persian Empire).

Gladius

The sword of the earlier Roman army, measuring about 60cm

Spatha

The sword of the late Roman Empire, longer than the gladius. The shape of the spatha continued in use during the early Middle Ages.

Great sword

A broad term generally referring to the knightly sword of the high Middle Ages.

Long-sword

A broad and somewhat ahistorical term, usually including the bastard-sword. Broadsword is a similarly ill-defined term.

Bastard

Sword or "hand and a half sword" - the traditional European, two-edged, straight sword for use with either one or two hands (see also Spadone).

Spadroon

A light sword used both to cut and to thrust

Zweihänder

The large and heavy, two-handed German sword of the 16th century.

Estoc

16th Century armor- and chainmail-piercing sword.

Schiavona

An Italian Renaissance broad sword.

Rapier

A longer European dueling sword, optimized more for thrusting than for a slashing action.

Small-sword

A very short and light descendant of the rapier, designed mostly for court use during the 18th and 19th centuries

Claymore

(Gaelic Claidheamh Mòr, meaning "great sword") - either of two types of Scottish sword; an older two-handed design used as an anti-cavalry weapon, and a more modern blade, famous as the "basket-hilted" claymore.

Épée

French for "sword", in English refers to the modern equivalent of the duelling sword.

Asian swords

Dao (pinyin dāo)

A Chinese single-edged curved sword, sometimes translated as sabre or broadsword in English.

Jian (pinyin jiąn)

A Chinese double-edged thin straight sword.

Saingeom

Ancient style of korean sword with a 90-centimeter (35 inch) long hammered blade from the Joseon dynasty. As many as 20 steps and craftsmen went into the manufacture of saingeom swords

Hwandudaedo

Ancient Korean sword from the Three Kingdoms era (4th to mid-7th centuries), exported from Korea to Japan before the 6th century. Numerous copies of this Korean long sword with a round handle have survived in Japan.

Katana and Tachi

Japanese samurai swords - see also Wakizashi and tanto.

Kampilan

Ancient Filipino sword. Traditionally, the kampilan measures about 40 to 44 inches in length, with a carved hilt, a single edge, and a pommel in the shape of “crocodile jaws.” The tip varies with spike or split teeth. Its cutting force compares with that of the Japanese katana.

Barong

A sword of the Tausugs of the southern Philippines that looks like an oversize and elongated leaf. The width of the blade make it more suitable for cutting than for thrusting.

Bolo

The most basic and widely-used sword in the Philippines, based on an agricultural machete. Typically, the bolo features rough and unfinished blades due to agricultural use. Variations include Tabak (more for cutting), and Tusok (more pointed, for thursting)

Pinute

A Filipino sword: long, straight, and well-balanced. It represents a variation on the agricultural bolo machete. The Visayan warriors of Cebu favour it.

Kris

Kris swords apparently originated in the 13th century on the island of Java in the Indonesian archipelago, and migrated to the Philippines, Malaysia, and various Southeast Asian countries.

Korambit

The Korambit developed in the Indonesian archipelago around the 13th century from roots in the Philippines and Malaysia.

Talibon

A short sword of the Christian community in the Phillipines. Its wooden grip has cane binding.

The word sword comes from the Old English sweord, cognate to Old High German swert, Middle Dutch swaert,

Old Norse sverð (cf.Danish sværd, Norwegian sverd, Swedish svärd) Old Frisian and Old Saxon swerd

and Modern Dutch zwaard and German Schwert,

from a Proto-Indo-European root *swer- "to wound, to cut".

A sword fundamentally consists of a blade and a hilt, typically with one or two edges for striking and cutting, and a point for thrusting. The basic intent and physics of swordsmanship have remained fairly constant through the centuries, but the actual techniques vary among cultures and periods as a result of the differences in blade design and purpose. Unlike the bow or spear, the sword is a purely military weapon, and this has made it symbolic of warfare or naked state power in many cultures. The names given to many swords in mythology, literature, and history reflect the high prestige of the weapon.

Attila the Hun's

sword, which he claimed was the sword of Mars, the Roman god of war

Bhawani

(Sword) - The

Sword given to Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj by Goddess Tuljabhavani.

Caladbolg

Sword of Fergus

mac Róich

Claíomh Solais

Sword of Nuada

Airgeadlámh, legendary king of Ireland

Crocea Mors

Sword of Julius

Caesar

Curtana

Sword of Ogier

the Dane, a legendary Danish hero, and a paladin of Charlemagne

Durendal

Sword of Roland, one of Charlemagne's paladins—alleged to be the same sword as the one wielded by Hector of Ilium

A sword that

belonged to Hector of Ilium

Excalibur/Caliburn/Caledflwch

Sword of King

Arthur

Fragarach

Sword of Manannan

mac Lir and Lugh Lamfada

Gram (Balmung) (Nothung)

Sword of

Siegfried, hero of the Nibelungenlied

Hauteclere

Sword of Olivier,

a French hero depicted in the Song of Roland

Heaven's Will/The Will of Heaven/Thuan Thien/Thuận Thiên

Sword of

Vietnamese King Le Loi

Hrunting

Sword lent to

Beowulf by Unferth, ineffective against Grendel's mother

Joyeuse

Sword of

Charlemagne

Totsuka no Tsurugi

The sword Susanoo

used to slay the Yamata no Orochi.

Kusanagi

Sword that

Susanoo found in the dead body of the Yamata no Orochi. It is one of three

Imperial Regalia of Japan, and also known as Ama-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi (天叢雲剣?).

Laevateinn

Sword that Surtr

will use to bring down the dome of heaven at Ragnarök.

Mimung

Sword that Wudga

inherits from his father Wayland the Smith

Lobera

The sword of the

king Saint Ferdinand III of Castile

Móralltach

The mythical

greatsword of the Celtic god Aéngus

Naegling

Sword of Beowulf

in his old age, used to fight the dragon

Philippan

Sword given to

Marc Antony by Cleopatra. Antony lost the sword when he was defeated by Octavian

at the Battle of Actium.

Shamshir-e Zomorrodnegar

Sword of King

Solomon(in Persian folklore)

Taming Sari

The Kris

belonging to the Malay warrior Hang Tuah of the Malacca Sultanate.

Tyrfing

Cursed sword that

causes eventual death to its wielder and their kin, it is said to bring about

three great evils.

The Lightsaber is a sword concept featured in the Star Wars universe. Its

popularity has inspired similar laser based swords to have been used in other

works of science fiction media.

The Zanbatou is an incredibly large type of Japanese sword with a mysterious

historical background. Most unrealistically large swords in Japanese media such

as the Buster Sword or the Tetsusaiga found in Japanese media today are inspired

by the Zanbatōu.

The Vorpal blade is a sword from the poem "Jabberwocky". It has since been

adapted into modern media as a type of magic sword that makes appearances in

unrelated fictional works. Similar magical swords have become common in fantasy

literature, games, and art, but this particular sword has had its name mentioned

in many varied works from various writers.

Excalibur is the sword of the legendary King Arthur.

The Sword of Godric Gryffindor, from the Harry Potter series.

Living swordsmiths and living history in the weaponry: six of the foremost swordmakers in Europe today according to

http://bjorn.foxtail.nu/masters_eng.htm

Pattern-welded Viking sword

Atlantean sword

Thieves' fantasy scimitar

Diamond hilt broadsword

Wave hilt broadsword

Vendel sword

Heavenly sword

Sword games

Fallen sword

Beyond the sword

Gun sword

Angel sword

E-sword

Sword of truth

But as the beautitudes

said...

"Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God."

And Samuel Colt's peacemaker was not the idea. Rather, it refers to those making

peaci with G*d, our most horrible a Harald.

The only negotiation is over surrender with Him.

Sivun ensimmäinen esimerkki miekoista on aitosuomalainen miekka. Kalpa eli kourain ei juurikaan suojannut rannetta iskuilta.

Ei oltu hyökkäävää soturikansaa vaan suojeltiin vaan kotejamme, "näillä raukoilla rajoilla, poloisilla pohjan mailla".

Suomensukuiset kansat olivat Venäjän "intiaaneja" ja alkuperäisväestö. Ajettiin pohjoiseen ja hävitettiin pois.

Vepsäläiset jokiensa varsilla, etymologia taitaa tulla sanasta vesi.

http://www.kp-art.fi/jt/

SATAKUNTA

Satakunnan laulu

Kauas missä katse kantaa yli peltojen,

missä kaartaa taivon rantaa salo sininen,

siellä Satakunnan kansa tyynnä kyntää aurallansa maata isien.

Täällä muinoin töin ja toimin raatoi rauhan mies,

luonnon voitti loitsuvoimin, synnyt syvät ties.

Kasvun kotipelto kantoi, raatajalle onnen antoi lämmin kotilies.

Koska Suomen viljelystä uhkaa sorron yö,

häätämään käy hävitystä täällä kansan työ.

Nousee Satakunnan kansa, entisellä voimallansa karhun kämmen lyö.

LARP

Live Action Role Play

"According to custom during the Viking age, it is known that all free Norsemen were required to own and carry weapons. The mandate to own and carry weapons was not only for defensive purposes but also to verify a Vikings social status within their clan. A typical wealthy Viking would have a complete ensemble made for them, consisting of a helmet, sword, shield and a chain mail shirt as well as various other armaments. While a man of lesser stature might only own a spear and a shield. With the spear, sword and shield being the basic armaments of a typical Viking warrior, the art of the blacksmith was especially essential."

http://vikinghelmets.org/blacksmiths-and-viking-swords/comment-page-1#comment-232

http://www.helsinki.fi/arkeologia/rautaesine/miekat/tutkimushistoria/tutkimustilanne.htm

"Vanhin rautakauden miekkojen perustutkimus on vuodelta 1916, jolloin ilmestyi Martin Jahnin "Die Befaffung der Germanen in der älteren Eisenzeit". Kyseinen teos on varsin täydellinen esitys ilmestymisojankohtanaan tunnetuista Pohjoiseurooppalaisista aseista. Kirja on varsin deskriptiivinen ja partikularisoiva. Jahn ei pyri määrittelemään tyyppejä. Tyyppitermien sijasta hän käyttää yleistermejä muotoa ”yksiteräiset miekat keisariaikana”. Yleistermien alaan lukeutuvien miekkojen yksityiskohtia hän luettelee järjestelmällisesti ja kattavasti. Jahnin aineistoon ei kuulu suomalaisia löytöjä, mutta suomalaiset tutkijat ovat hyödyntäneet hänen teostaan omissa tutkimuksissaan.

Varhaisen roomalaisajan vuoteen 1968 asti Suomesta löytyneet edustajat on tyypitelty Unto Salon väitöskirjassa ”Die Frühromische Zeit in Finnland”. Salo palaa uudelleen aiheeseen vuonna 1984 ilmestyneessä artikkelissa ”On Weapondry of Early Roman period” . Esa Suomisen pro gradu -työ ”Suomen nuoremman roomalaisajan aseet” käsittelee nimensä mukaisesti seuraavan periodin aseita miekkoineen. Kansainvaellusajan miekoista ei ole erikoistutkimusta, mutta niitä on muun aineiston ohella käsitellyt mm. Marianne Schauman-Lönnqvist useissa yhteyksissä (1992, 1996).

Helmer Salmo (1938) on luonut oman typologian merovigiaikaisista miekkalöydöistämme. Hänen tutkimuksensa ilmestymisajankohtana ei Pohjois-Euroopan aineistosta vielä ollut saatavissa yleiseurooppalaista luokittelua. Tämän julkaisi Elias Behmer vuonna 1939. ”Das Zweischneidige Schwert der Germanische Völkerwandrungszeit" on klassinen teos pohjoiseurooppalaisista ”vanhemman ja nuoremman kansainvaellusajan” miekoista. Nykyisin kyseisiä periodeja nimitetään meillä kansainvaellusajaksi ja merovingiajaksi. Behmer on kirjallisuuden perusteella huomioinut myös osan suomalaisista kyseisen ajanjakson miekoista ja tyypittänyt ne. Tässä yhteydessä on huomioitu sekä Behmerin että Salmon merovingiajan miekkojen luokitukset, jotka ovat osin poikkeavat.

Meillä merovingiajan miekkoja käsittelee yleiseurooppalaisten luokitusten pohjalta jonkin verran myös Nils Cleve (1943). Viikinkiajan miekoista ja muistakin aseista ilmestyi vuonna 1919 Jan Petersenin pääosin norjalaiseen aineistoon perustuva tutkimus ”Norske Vikingesverd. En typologisk-kronologisk studie over vikngetiden vaaben”. Petersenin alkuperäisaineisto on norjalaista, mutta koska Norjasta tunnettiin jo tuolloin hyvin laaja aineisto ja useimmat miekat ovat viikinkiajalla käytössä koko Euroopassa, hänen tutkimukseensa sisältyy lähes kaikki meiltäkin löytyneet tyypit. Petersenin teoksessa on joitain viittauksia myös suomalaiseen aineistoon.

Petersen jakoi aineiston 26 päätyyppiin ja 20 erikoistyyppiin, jolla nykyisin tarkoitettaisiin lähinnä alatyyppiä. Brittiläinen tutkija Ewart Oakeshott toteaa vuonna 2000, että mitään Petersenin työtä vastaavaa ei ole edes tarpeen tehdä, koska hänen työnsä on niin vankkaa. Ylistyksestä huolimatta Oakeshott itse soveltaa miekkoihin toista luokitusjärjestelmää, joka on vähemmän rönsyilevä. Wheeler jakoi vuonna 1927 viikinkiajan miekat pääosin brittiläisen materiaalin pohjalta seitsemään tyyppiin. Oakeshott laajensi tätä luokittelua vuonna 1960 lisäämällä siihen kaksi uutta tyyppiä, jolloin tyyppien kokonaismääräksi tuli yhdeksän. Tässä esityksessä pitäydytään Petersenin typologiassa sen ylenpalttisuudesta huolimatta, koska meidän aineistoamme on tutkittu nimenomaan sen ehdoin. Milloin yksittäisistä, kuvatuista miekoista on saatavissa Wheelerin ja Oakeshottin tyypityksiä, ne mainitaan Petersenin tyyppien yhteydessä.

Petersenin tyypityksen eittämätön vahvuus tulee ilmi myös siinä, että Mikael Jakobsson (1992) on viikinkiajan miekkojen tutkimuksessaan säilyttänyt Petersenin luokituksen. Petersenin systematiikan rinnalle hän on kuitenkin luonut toisen, ns. muotoiluperiaatteisiin perustuvan luokittelun. Jakobssonin muotoluperiaatteet eivät ole tyyppejä toisella nimellä. Artefakti voidaan lukea vain yhteen tyyppiin yhdessä typologisessa systeemissä. Jakobssonin muotoilupereiaatteille on taas ominaista, että yksi esine tai tyyppi voi kuulua useamman muotoiluperiaatteen piiriin. Periaatteiden tarkoituksena on kiinnittää huomiota siihen, että artefaktit ovat perimmiltään tuotteita, eivät staattisia kappaleita. Muotoiluperiaatteiden avulla voidaan tuottaa selityksen kohteeksi erilaisia alueellisia ja ajallisia jakaumia kuin tyyppien avulla. Jacobsonin on tutustunut aineistoonsa pääosin kirjallisuuden avulla. Se käsittää periaatteessa koko Pohjois-Euroopan. Valitettavasti hän ei tunne eräitä keskeisiä suomalaisia julkaisuja, kuten Lehtosalo-Hilander 1985 ja Kivikoski 1973.

Suomen viikinkiajan, jossain määrin myös ristiretkiajan, miekkoja käsittelee Pirkko-Liisa Lehtosalo-Hilander useissa julkaisuissaan. Tässä yhteydessä näistä tärkein on Lehtosalo-Hilanderin vuonna 1985 Suomen Museossa ilmestynyt ”Viikinkiajan aseista. Leikkiä luvuilla ja lohikäärmeillä”.

Ewart Oakeshott on kirjoittanut johdantoluvun Ian Peircen toimittamaan teokseen ”Swords of The Viking Age”. Teos on moderni johdatus aiheeseen, jossa Peirce itse vastaa laajan esimerkkianeiston esittelystä. Luokittelua ja ajoituksia käsittelevän luvun on kirjoittanut Lee A. Jones.

Englantilainen Ewart Oakeshott on luonut meidän ristiretkiaikaamme vastaavan ajanjakson käytetyimmän Eurooppalaisten miekkojen luokituksen. Hän on huomioinut tässä myös meiltä löytynyttä, erityisesti Jorma Leppäahon muistiinpanoihin perustuvaa aineistoa, joka ilmestyi postuumisti v. 1964. Leppäahon teos sisältää kuvauksia yksittäisistä miekoista, se ei ole varsinaisesti tutkimus. Leppäaho on vaikuttanut paljon eurooppalaiseen miekkatutkimukseen, mm. juuri Oakeshottiin osoittamalla, että monet aiemmin 1200–1300 luvuille kuuluviksi katsottujen miekkatyppien käyttö on suomalaisten hautalöytöjen perusteella alkanut jo 1000-luvun alussa.

Leena Tomanterä (1978) on suomalaisen aineiston pohjalta luonut tyypityksen kiekkopontisille miekoille. Hän on myös luokitellut myöhäisrautakautiset säiläkirjoitukset pyrkimyksenään identifioida eri seppämestarit tai työpajat. Miekkojen kansainvälisen levinnän ja Suomen pienehkön aineiston takia suomalaiset tutkijat ovat yleensä määritelleet Suomen löydöt muualla luotujen typologioiden avulla. Leena Tomanterä käsittelee jo mainitussa julkaisussaan ristiretkiajan miekkoja. Edellisten lisäksi miekkoja käsitellään lukuisissa muissa julkaisuissa, useimmiten muiden löytöjen ohella.

Ella Kivikoski (1973) luettelee kattavasti esimerkkejä ilmestymisaikanaan tunnetuista rautakautisista esineistä, myös miekoista. Kivikoski ei määrittele tyyppejä, hän vain ilmoittaa, että tietty esine kuuluu tiettyyn tyyppiin. Tyyppimäärittelyn korvaa kuva esimerkkiesineestä. Ajatus taustalla lienee se, että ”yksi kuva puhuu enemmän kuin tuhat sanaa”. Tämä pitää osin paikkansa, mutta yhtä lailla pitää paikkansa, että yksi kuva voidaan ”lukea” tuhannella eri tavalla. Toisin sanoen, ilman tekstiä, jossa kiinnitetään huomiota esineen tiettyihin piirteisiin, ei kuva määrittele mitään. Teoksen käyttäjä ei voi tietää, mitkä omaisuudet kuvassa olevassa esineessä ovat niitä, joiden johdosta esine kuuluu tiettyyn tyyppiin, mitkä taas satunnaisia tämän kannalta."

Kalevala Epic

Birth of Väinämöinen

Väinämöinen's Sowing

Väinämöinen and Joukahainen

The Fate of Aino

Väinämöinen's Fishing

Joukahainen's Crossbow

Väinämöinen Meets Louhi

Väinämöinen's Wound

Origin of Iron

Ilmarinen Forges the Sampo

Lemminkäinen and Kyllikki

Kyllikki's Broken Vow

The Elk of Hiisi

Lemminkäinen's trials and death

Lemminkäinen's Restoration

Väinämöinen's Boat-building

Väinämöinen and Antero Vipunen

Väinämöinen and Ilmarinen, Rival Suitors

Ilmarinen's trials and betrothal

The Brewing of Beer

Ilmarinen's Wedding-feast

The Tormenting of the Bride

Osmotar Advises the Bride

The departure of the bride and bridegroom

The homecoming of the bride and bridegroom

Lemminkäinen's journey to Pohjola

The duel at Pohjola

Lemminkäinen's mother

The Isle of Refuge

Lemminkäinen and Tiera

Untamo and Kullervo

Kullervo As A Shepherd

The Death of Ilmarinen's Wife

Kullervo finds his family

Kullervo finds his sister

Kullervo's Victory and Death

Ilmarinen's Bride of Gold

Ilmarinen's Fruitless Wooing

The Expedition Against Pohjola

The Pike and The Kantele

Väinämöinen's Music

The Recovery of the Sampo

The Sampo Lost In the Sea

The Birth of the Second Harp

Louhi's Pestilence on Kalevala

Otso, the Bear

The Robbery of the Sun, Moon and Fire

Capture of the Fire-fish

Restoration of the Sun and Moon

Marjatta

The Birth of Iron

Rune IX, Origin of Iron

WAINAMOINEN, thus encouraged,

Quickly rises in his snow-sledge,

Asking no one for assistance,

Straightway hastens to the cottage,

Takes a seat within the dwelling.

Come two maids with silver pitchers,

Bringing also golden goblets;

Dip they up a very little,

But the very smallest measure

Of the blood of the magician,

From the wounds of Wainamoinen.

From the fire-place calls the old man,

Thus the gray-beard asks the minstrel:

"Tell me who thou art of heroes,

Who of all the great magicians?

Lo! thy blood fills seven sea-boats,

Eight of largest birchen vessels,

Flowing from some hero's veinlets,

From the wounds of some magician.

Other matters I would ask thee;

Sing the cause of this thy trouble,

Sing to me the source of metals,

Sing the origin of iron,

How at first it was created."

Then the ancient Wainamoinen

Made this answer to the gray-beard:

"Know I well the source of metals,

Know the origin of iron;

f can tell bow steel is fashioned.

Of the mothers air is oldest,

Water is the oldest brother,

And the fire is second brother,

And the youngest brother, iron;

Ukko is the first creator.

Ukko, maker of the heavens,

Cut apart the air and water,

Ere was born the metal, iron.

Ukko, maker of the heavens,

Firmly rubbed his hands together,

Firmly pressed them on his knee-cap,

Then arose three lovely maidens,

Three most beautiful of daughters;

These were mothers of the iron,

And of steel of bright-blue color.

Tremblingly they walked the heavens,

Walked the clouds with silver linings,

With their bosoms overflowing

With the milk of future iron,

Flowing on and flowing ever,

From the bright rims of the cloudlets

To the earth, the valleys filling,

To the slumber-calling waters.

"Ukko's eldest daughter sprinkled

Black milk over river channels

And the second daughter sprinkled

White milk over hills and mountains,

While the youngest daughter sprinkled

Red milk over seas and oceans.

Whero the black milk had been sprinked,

Grew the dark and ductile iron;

Where the white milk had been sprinkled.

Grew the iron, lighter-colored;

Where the red milk had been sprinkled,

Grew the red and brittle iron.

"After Time had gone a distance,

Iron hastened Fire to visit,

His beloved elder brother,

Thus to know his brother better.

Straightway Fire began his roarings,

Labored to consume his brother,

His beloved younger brother.

Straightway Iron sees his danger,

Saves himself by fleetly fleeing,

From the fiery flame's advances,

Fleeing hither, fleeing thither,

Fleeing still and taking shelter

In the swamps and in the valleys,

In the springs that loudly bubble,

By the rivers winding seaward,

On the broad backs of the marshes,

Where the swans their nests have builded,

Where the wild geese hatch their goslings.

"Thus is iron in the swamp-lands,

Stretching by the water-courses,

Hidden well for many ages,

Hidden in the birchen forests,

But he could not hide forever

From the searchings of his brother;

Here and there the fire has caught him,

Caught and brought him to his furnace,

That the spears, and swords, and axes,

Might be forged and duly hammered.

In the swamps ran blackened waters,

From the heath the bears came ambling,

And the wolves ran through the marshes.

Iron then made his appearance,

Where the feet of wolves had trodden,

Where the paws of bears had trampled.

"Then the blacksmith, Ilmarinen,

Came to earth to work the metal;

He was born upon the Coal-mount,

Skilled and nurtured in the coal-fields;

In one hand, a copper hammer,

In the other, tongs of iron;

In the night was born the blacksmith,

In the morn he built his smithy,

Sought with care a favored hillock,

Where the winds might fill his bellows;

Found a hillock in the swamp-lands,

Where the iron hid abundant;

There he built his smelting furnace,

There he laid his leathern bellows,

Hastened where the wolves had travelled,

Followed where the bears had trampled,

Found the iron's young formations,

In the wolf-tracks of the marshes,

In the foot-prints of the gray-bear.

"Then the blacksmith, Ilmarinen,

'Thus addressed the sleeping iron:

Thou most useful of the metals,

Thou art sleeping in the marshes,

Thou art hid in low conditions,

Where the wolf treads in the swamp-lands,

Where the bear sleeps in the thickets.

Hast thou thought and well considered,

What would be thy future station,

Should I place thee in the furnace,

Thus to make thee free and useful?'

"Then was Iron sorely frightened,

Much distressed and filled with horror,

When of Fire he heard the mention,

Mention of his fell destroyer.

"Then again speaks Ilmarinen,

Thus the smith addresses Iron:

'Be not frightened, useful metal,

Surely Fire will not consume thee,

Will not burn his youngest brother,

Will not harm his nearest kindred.

Come thou to my room and furnace,

Where the fire is freely burning,

Thou wilt live, and grow, and prosper,

Wilt become the swords of heroes,

Buckles for the belts of women.'

"Ere arose the star of evening,

Iron ore had left the marshes,

From the water-beds had risen,

Had been carried to the furnace,

In the fire the smith had laid it,

Laid it in his smelting furnace.

Ilmarinen starts the bellows,

Gives three motions of the handle,

And the iron flows in streamlets

From the forge of the magician,

Soon becomes like baker's leaven,

Soft as dough for bread of barley.

Then out-screamed the metal, Iron:

'Wondrous blacksmith, Ilmarinen,

Take, O take me from thy furnace,

From this fire and cruel torture.'

"Ilmarinen thus made answer:

'I will take thee from my furnace,

'Thou art but a little frightened,

Thou shalt be a mighty power,

Thou shalt slay the best of heroes,

Thou shalt wound thy dearest brother.'

"Straightway Iron made this promise,

Vowed and swore in strongest accents,

By the furnace, by the anvil,

By the tongs, and by the hammer,

These the words he vowed and uttered:

'Many trees that I shall injure,

Shall devour the hearts of mountains,

Shall not slay my nearest kindred,

Shall not kill the best of heroes,

Shall not wound my dearest brother;

Better live in civil freedom,

Happier would be my life-time,

Should I serve my fellow-beings,

Serve as tools for their convenience,

Than as implements of warfare,

Slay my friends and nearest. kindred,

Wound the children of my mother.'

"Now the master, Ilmarinen,

The renowned and skilful blacksmith,

From the fire removes the iron,

Places it upon the anvil,

Hammers well until it softens,

Hammers many fine utensils,

Hammers spears, and swords, and axes,

Hammers knives, and forks, and hatchets,

Hammers tools of all descriptions.

"Many things the blacksmith needed,

Many things he could not fashion,

Could not make the tongue of iron,

Could not hammer steel from iron,

Could not make the iron harden.

Well considered Ilmarinen,

Deeply thought and long reflected.

Then he gathered birchen ashes,

Steeped the ashes in the water,

Made a lye to harden iron,

Thus to form the steel most needful.

With his tongue he tests the mixture,

Weighs it long and well considers,

And the blacksmith speaks as follows:

'All this labor is for nothing,

Will not fashion steel from iron,

Will not make the soft ore harden.'

"Now a bee flies from the meadow,

Blue-wing coming from the flowers,

Flies about, then safely settles

Near the furnace of the smithy.

"'Thus the smith the bee addresses,

These the words of Ilmarinen:

'Little bee, thou tiny birdling,

Bring me honey on thy winglets,

On thy tongue, I pray thee, bring me

Sweetness from the fragrant meadows,

From the little cups of flowers,

From the tips of seven petals,

That we thus may aid the water

To produce the steel from iron.'

"Evil Hisi's bird, the hornet,

Heard these words of Ilmarinen,

Looking from the cottage gable,

Flying to the bark of birch-trees,

While the iron bars were heating

While the steel was being tempered;

Swiftly flew the stinging hornet,

Scattered all the Hisi horrors,

Brought the blessing of the serpent,

Brought the venom of the adder,

Brought the poison of the spider,

Brought the stings of all the insects,

Mixed them with the ore and water,

While the steel was being, tempered.

"Ilmarinen, skilful blacksmith,

First of all the iron-workers,

Thought the bee had surely brought him

Honey from the fragrant meadows,

From the little cups of flowers,

From the tips of seven petals,

And he spake the words that follow:

'Welcome, welcome, is thy coming,

Honeyed sweetness from the flowers

Thou hast brought to aid the water,

Thus to form the steel from iron!'

"Ilmarinen, ancient blacksmith,

Dipped the iron into water,

Water mixed with many poisons,

Thought it but the wild bee's honey;

Thus he formed the steel from iron.

When he plunged it into water,

Water mixed with many poisons,

When be placed it in the furnace,

Angry grew the hardened iron,

Broke the vow that he had taken,

Ate his words like dogs and devils,

Mercilessly cut his brother,

Madly raged against his kindred,

Caused the blood to flow in streamlets

From the wounds of man and hero.

This, the origin of iron,

And of steel of light blue color."

From the hearth arose the gray-beard,

Shook his heavy looks and answered:

"Now I know the source of iron,

Whence the steel and whence its evils;

Curses on thee, cruel iron,

Curses on the steel thou givest,

Curses on thee, tongue of evil,

Cursed be thy life forever!

Once thou wert of little value,

Having neither form nor beauty,

Neither strength nor great importance,

When in form of milk thou rested,

When for ages thou wert hidden

In the breasts of God's three daughters,

Hidden in their heaving bosoms,

On the borders of the cloudlets,

In the blue vault of the heavens.

"Thou wert once of little value,

Having neither form nor beauty,

Neither strength nor great importance,

When like water thou wert resting

On the broad back of the marshes,

On the steep declines of mountains,

When thou wert but formless matter,

Only dust of rusty color.

"Surely thou wert void of greatness,

Having neither strength nor beauty,

When the moose was trampling on thee,

When the roebuck trod upon thee,

When the tracks of wolves were in thee,

And the bear-paws scratched thy body.

Surely thou hadst little value

When the skilful Ilmarinen,

First of all the iron-workers,

Brought thee from the blackened swamp-lands,

Took thee to his ancient smithy,

Placed thee in his fiery furnace.

Truly thou hadst little vigor,

Little strength, and little danger,

When thou in the fire wert hissing,

Rolling forth like seething water,

From the furnace of the smithy,

When thou gavest oath the strongest,

By the furnace, by the anvil,

By the tongs, and by the hammer,

By the dwelling of the blacksmith,

By the fire within the furnace.

"Now forsooth thou hast grown mighty,

Thou canst rage in wildest fury;

Thou hast broken all thy pledges,

All thy solemn vows hast broken,

Like the dogs thou shamest honor,

Shamest both thyself and kindred,

Tainted all with breath of evil.

Tell who drove thee to this mischief,

Tell who taught thee all thy malice,

Tell who gavest thee thine evil!

Did thy father, or thy mother,

Did the eldest of thy brothers,

Did the youngest of thy sisters,

Did the worst of all thy kindred

Give to thee thine evil nature?

Not thy father, nor thy mother,

Not the eldest of thy brothers,

Not the youngest of thy sisters,

Not the worst of all thy kindred,

But thyself hast done this mischief,

Thou the cause of all our trouble.

Come and view thine evil doings,

And amend this flood of damage,

Ere I tell thy gray-haired mother,

Ere I tell thine aged father.

Great indeed a mother's anguish,

Great indeed a father's sorrow,

When a son does something evil,

When a child runs wild and lawless.

"Crimson streamlet, cease thy flowing

From the wounds of Wainamoinen;

Blood of ages, stop thy coursing

From the veins of the magician;

Stand like heaven's crystal pillars,

Stand like columns in the ocean,

Stand like birch-trees in the forest,

Like the tall reeds in the marshes,

Like the high-rocks on the sea-coast,

Stand by power of mighty magic!

"Should perforce thy will impel thee,

Flow thou on thine endless circuit,

Through the veins of Wainamoinen,

Through the bones, and through the muscles,

Through the lungs, and heart, and liver,

Of the mighty sage and singer;

Better be the food of heroes,

Than to waste thy strength and virtue

On the meadows and the woodlands,

And be lost in dust and ashes.

Flow forever in thy circle;

Thou must cease this crimson out-flow;

Stain no more the grass and flowers,

Stain no more these golden hill-tops,

Pride and beauty of our heroes.

In the veins of the magician,

In the heart of Wainamoinen,

Is thy rightful home and storehouse.

Thither now withdraw thy forces,

Thither hasten, swiftly flowing;

Flow no more as crimson currents,

Fill no longer crimson lakelets,

Must not rush like brooks in spring-tide,

Nor meander like the rivers.

"Cease thy flow, by word of magic,

Cease as did the falls of Tyrya,

As the rivers of Tuoni,

When the sky withheld her rain-drops,

When the sea gave up her waters,

In the famine of the seasons,

In the years of fire and torture.

If thou heedest not this order,

I shall offer other measures,

Know I well of other forces;

I shall call the Hisi irons,

In them I shall boil and roast thee,

Thus to check thy crimson flowing,

Thus to save the wounded hero.

"If these means be inefficient,

Should these measures prove unworthy,

I shall call omniscient Ukko,

Mightiest of the creators,

Stronger than all ancient heroes,

Wiser than the world-magicians;

He will check the crimson out-flow,

He will heal this wound of hatchet.

"Ukko, God of love and mercy,

God and Master Of the heavens,

Come thou hither, thou art needed,

Come thou quickly I beseech thee,

Lend thy hand to aid thy children,

Touch this wound with healing fingers,

Stop this hero's streaming life-blood,

Bind this wound with tender leaflets,

Mingle with them healing flowers,

Thus to check this crimson current,

Thus to save this great magician,

Save the life of Wainamoinen."

Thus at last the blood-stream ended,

As the magic words were spoken.

Then the gray-beard, much rejoicing,

Sent his young son to the smithy,

There to make a healing balsam,

From the herbs of tender fibre,

From the healing plants and flowers,

From the stalks secreting honey,

From the roots, and leaves, and blossoms.

On the way he meets an oak-tree,

And the oak the son addresses:

"Hast thou honey in thy branches,

Does thy sap run full of sweetness?"

Thus the oak-tree wisely answers:

"Yea, but last night dripped the honey

Down upon my spreading branches,

And the clouds their fragrance sifted,

Sifted honey on my leaflets,

From their home within the heavens."

Then the son takes oak-wood splinters,

Takes the youngest oak-tree branches,

Gathers many healing grasses,

Gathers many herbs and flowers,

Rarest herbs that grow in Northland,

Places them within the furnace

In a kettle made of copper;

Lets them steep and boil together,

Bits of bark chipped from the oak-tree,

Many herbs of healing virtues;

Steeps them one day, then a second,

Three long days of summer weather,

Days and nights in quick succession;

Then he tries his magic balsam,

Looks to see if it is ready,

If his remedy is finished;

But the balsam is unworthy.

Then he added other grasses,

Herbs of every healing virtue,

That were brought from distant nations,

Many hundred leagues from Northland,

Gathered by the wisest minstrels,

Thither brought by nine enchanters.

Three days more be steeped the balsam,

Three nights more the fire be tended,

Nine the days and nights be watched it,

Then again be tried the ointment,

Viewed it carefully and tested,

Found at last that it was ready,

Found the magic balm was finished.

Near by stood a branching birch-tree.

On the border of the meadow,

Wickedly it had been broken,

Broken down by evil Hisi;

Quick he takes his balm of healing,

And anoints the broken branches,

Rubs the balsam in the fractures,

Thus addresses then the birch-tree:

"With this balsam I anoint thee,

With this salve thy wounds I cover,

Cover well thine injured places;

Now the birch-tree shall recover,

Grow more beautiful than ever."

True, the birch-tree soon recovered,

Grew more beautiful than ever,

Grew more uniform its branches,

And its bole more strong and stately.

Thus it was be tried the balsam,

Thus the magic salve he tested,

Touched with it the splintered sandstone,

Touched the broken blocks of granite,

Touched the fissures in the mountains,

And the broken parts united,

All the fragments grew together.

Then the young boy quick returning

With the balsam he had finished,

To the gray-beard gave the ointment,

And the boy these measures uttered

"Here I bring the balm of healing,

Wonderful the salve I bring thee;

It will join the broken granite,

Make the fragments grow together,

Heat the fissures in the mountains,

And restore the injured birch-tree."

With his tongue the old man tested,

Tested thus the magic balsam,

Found the remedy effective,

Found the balm had magic virtues;

Then anointed he the minstrel,

Touched the wounds of Wainamoinen,

Touched them with his magic balsam,

With the balm of many virtues;

Speaking words of ancient wisdom,

These the words the gray-beard uttered:

"Do not walk in thine own virtue,

Do not work in thine own power,

Walk in strength of thy Creator;

Do not speak in thine own wisdom,

Speak with tongue of mighty Ukko.

In my mouth, if there be sweetness,

It has come from my Creator;

If my bands are filled with beauty,

All the beauty comes from Ukko."

When the wounds had been anointed,

When the magic salve had touched them,

Straightway ancient Wainamoinen

Suffered fearful pain and anguish,

Sank upon the floor in torment,

Turning one way, then another,

Sought for rest and found it nowhere,

Till his pain the gray-beard banished,

Banished by the aid of magic,

Drove away his killing torment

To the court of all our trouble,

To the highest hill of torture,

To the distant rocks and ledges,

To the evil-bearing mountains,

To the realm of wicked Hisi.

Then be took some silken fabric,

Quick he tore the silk asunder,

Making equal strips for wrapping,

Tied the ends with silken ribbons,

Making thus a healing bandage;

Then he wrapped with skilful fingers

Wainamoinen's knee and ankle,

Wrapped the wounds of the magician,

And this prayer the gray-beard uttered

"Ukko's fabric is the bandage,

Ukko's science is the surgeon,

These have served the wounded hero,

Wrapped the wounds of the magician.

Look upon us, God of mercy,

Come and guard us, kind Creator,

And protect us from all evil!

Guide our feet lest they may stumble,

Guard our lives from every danger,

From the wicked wilds of Hisi."

Wainamoinen, old and truthful,

Felt the mighty aid of magic,

Felt the help of gracious Ukko,

Straightway stronger grew in body,

Straightway were the wounds united,

Quick the fearful pain departed.

Strong and hardy grew the hero,

Straightway walked in perfect freedom,

Turned his knee in all directions,

Knowing neither pain nor trouble.

Then the ancient Wainamoinen

Raised his eyes to high Jumala,

Looked with gratitude to heaven,

Looked on high, in joy and gladness,

Then addressed omniscient Ukko,

This the prayer the minstrel uttered:

"O be praised, thou God of mercy,

Let me praise thee, my Creator,

Since thou gavest me assistance,

And vouchsafed me thy protection,

Healed my wounds and stilled mine anguish,

Banished all my pain and trouble,

Caused by Iron and by Hisi.

O, ye people of Wainola,

People of this generation,

And the folk of future ages,

Fashion not in emulation,

River boat, nor ocean shallop,

Boasting of its fine appearance,

God alone can work completion,

Give to cause its perfect ending,

Never hand of man can find it,

Never can the hero give it,

Ukko is the only Master."

Pelasta elämä - lahjoita verta!

Safe a Life - Donate Blood!